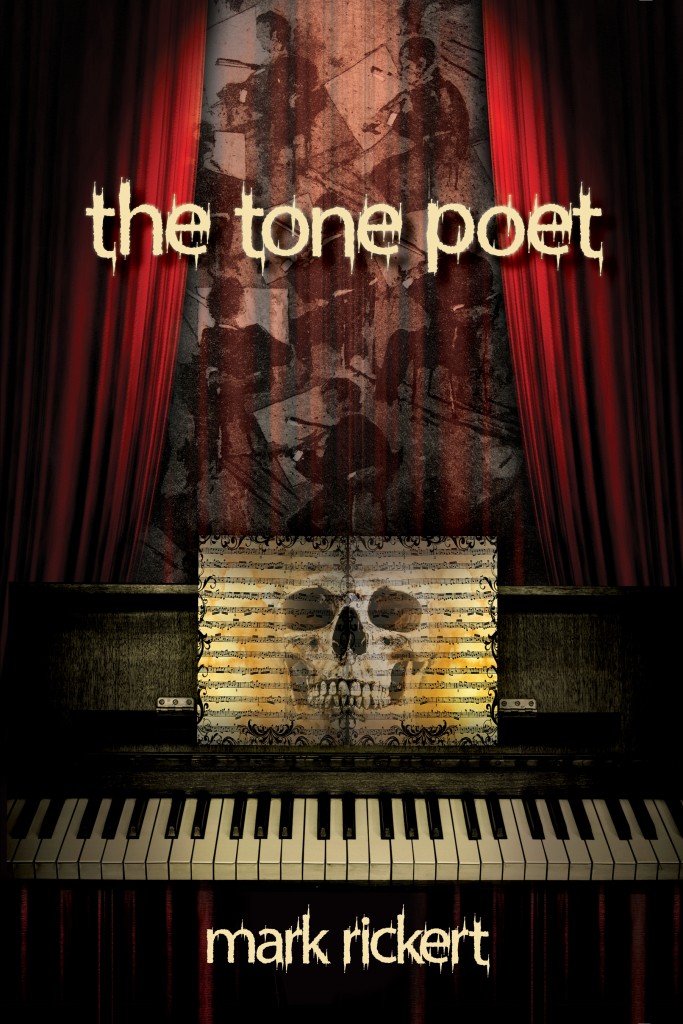

Mark Rickert’s first book, The Tone Poet, is a gripping read filled with thrill, dark fantasy, and gore.

Mark Rickert’s first book, The Tone Poet, is a gripping read filled with thrill, dark fantasy, and gore.

About the Author

Mark Rickert was born in Nashville, Tennessee. The grandson of songwriter and country music manager Merle Kilgore, he was brought up in the peripherals of Nashville’s entertainment business. He served eight years as a journalist in the US Army Reserves while spending a year in Baghdad during Operation Iraqi Freedom where he wrote for various military publications.

After he returned home, he earned his master’s degree in English literature at Middle Tennessee State University.

He currently acts as chief of public affairs for the US Army Baltimore Recruiting Battalion at the Fort G. Meade military installation. He is a contributor to the Recruiter Journal, a monthly publication for the members of the US Army Recruiting Command stationed across the country.

He lives with his wife and daughter in Annapolis, Maryland.

Mark was recently interviewed by the The Tennessean.

Mark has this to say about writing his debut novel The Tone Poet:

I wanted to write horror stories at a very young age. I mostly blame my father for this. He hoarded paperback novels and even turned the garage into a kind of library with walls packed with pulp fiction novels written by Stephen King, H.P. Lovecraft, and Peter Straub. He also hung model spaceships by fish wire from the ceiling and nailed movie posters to the wall—posters like Alien and A Clockwork Orange. I spent a lot of time in that room, sifting through floppy-eared novels before I could even read, and when I finally got the knack of it, my dad encouraged me and my brothers by bribing us—he paid us a buck for every novel we got through. Looking back, I think the first dollar I ever pocketed was earned from reading a book.

But let’s face it. Most kids start off with fanciful dreams, like wanting to become the president of the United States or an astronaut, and I think most kids eventually let them go along the way, like a snake shedding its skin. That’s probably the norm. But that’s not my story. I didn’t shed the skin so much as cling to it out of desperation.

When I was maybe fourteen years old, I got hooked on playing with fire. I’d take my toys outside and torch them because it made for grand special effects. Eventually, I got more creative with my experiments. I made flamethrowers with aerosol cans and fireballs with my dad’s English Leather cologne. I would douse tabletops with rubbing alcohol, light it, and watch the liquid combust into seemingly harmless flames. You could hold a ball of fire in the palm of your hand and not burn yourself.

It was exciting, but as they say, it’s all fun and games until someone gets hurt, and in retrospect, it never occurred to me that my pyro-playtime correlated with my parents’ divorce, with my mother’s eating disorder, or with my childhood’s approaching end.

Things came to a head the day I skipped school to play with fire. I conducted my experiments in my dad’s library. A desk in the corner became my makeshift libratory table. I entertained myself with rubbing alcohol and matches . . . until I found myself standing there with my arm on fire. Woosh. I slapped at the flames with a dishrag, but then it caught fire, too. The terror that I had lost control nearly overwhelmed me. I jerked the backdoor open and threw the flaming rag outside, and then I got busy putting out my arm. Can anyone say drop and roll? In the shaky aftermath, I went to the bathroom and washed up, amazed at my luck, having escaped without burning myself to death. But in the meantime I’d forgotten all about the flaming dish rag, and by the time I returned to the library, a bigger fire had started outside, and now flames were licking up through the gaps around the backdoor. The drop ceiling tile caught fire. I tried to stop it—I went and filled a jug with water and splashed at the flames—but it was too late. The fire was spreading fast and melting plastic was falling all around me.

From that point, it was all about survival. I grabbed my dog and ran outside, and from the front lawn, I watched smoke coughing up from the rooftop. In moments there were sirens, and soon a couple of fire trucks came squeezing down our narrow street. Firemen spilled out of those trucks and squirted water all over the house until the flames went out and then they left.

The fire destroyed everything—my clothes, my books, my toys—and worse, it destroyed everything my brothers owned too. And everything my parents owned. And it gets worse. We didn’t have home insurance. My dad told me this on the front lawn while the house was still smoldering. Of course, this wasn’t my fault—this was my dad’s responsibility—but try telling that to a fourteen-year-old kid who just burned his house down; it wouldn’t matter to him, and it certainly didn’t matter to me. I shouldered the blame for that too. I shouldered the blame for everything.

Obviously, my family suffered a traumatic blow. I come from a loving household, but the family quilt had come unraveled long before I set fire to that house. The fire was only an outcome of darker undercurrents; an outward expression of a dysfunctional family in the grip of eating disorders, drug addiction, and alcoholism. In the following years, I wanted to end my life. I was hurting inside, and no one thought to ask me how I was doing. Eventually I came up with a plan to rectify my screw up. I would jump off the Briley Parkway Bridge and end it all. I already knew how to access the catwalk along the underbelly of graffiti-painted trestles. This would be a fitting and even romantic finale to my broken life.

I kicked around this idea for the next two years, all the while working up the nerve to go through with it, and by sixteen the idea was just sort of part of me. Then one day while walking to meet a friend, I was struck with a marvelous idea. What if, instead of throwing myself off a bridge, I went after my dream and committed my life to becoming a writer? The idea was so good that I had to sit down on the side of the road. I’d always known, even as a kid, that the hope of becoming a novelist was farfetched. But now what did I have to lose? I had nothing. Absolutely nothing.

So I made a pact with myself. I promised to devote my life to writing, and in return, I would get on with my life and give up this idea of doing away with myself. The parts of my fractured self shook hands, and from that moment on I had purpose, and I’m fairly certain it saved my life. At the least, it kept me going.

That was a long time ago. Even so I never forgot my agreement. I wrote short stories for the next few years but nothing much came of it. I went to college and earned a bachelor’s in English. At twenty-three, I joined the Army Reserve as a photo-journalist. When I was called to duty in 2003, I started writing my first novel in Baghdad, Iraq. I wrote for two hours each day: not much, but it got me through that long year. Of course, the reality of writing proved much more difficult than the dream of writing, and it took me another nine years of rewriting and restructuring before I finished my first novel, The Tone Poet.

In many ways, it was this novel that got me out of that mess, and I think back to my dad’s library, with all those bookshelves bending beneath the weight of paperbacks, and I can’t help but wonder, would my book have a place on those shelves? I think so. In fact I’m sure of it.

Connect with the Author

You can visit Mark’s website at markrickertauthor.com. You can also follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

About the Book

The Tone Poet is a double award-winner!

- Eric Hoffer Book Awards 2015 Finalist

- eLit Awards 2015 Bronze Medal for Horror

The Tone Poet is available in the BQB online store. All versions (print and eBook) are available through the following retailers, as well as all other major book and eBook retailers: